My review of a brilliant show revisiting public access broadcasting in the 1970s, at Raven Row, London, for ArtReview

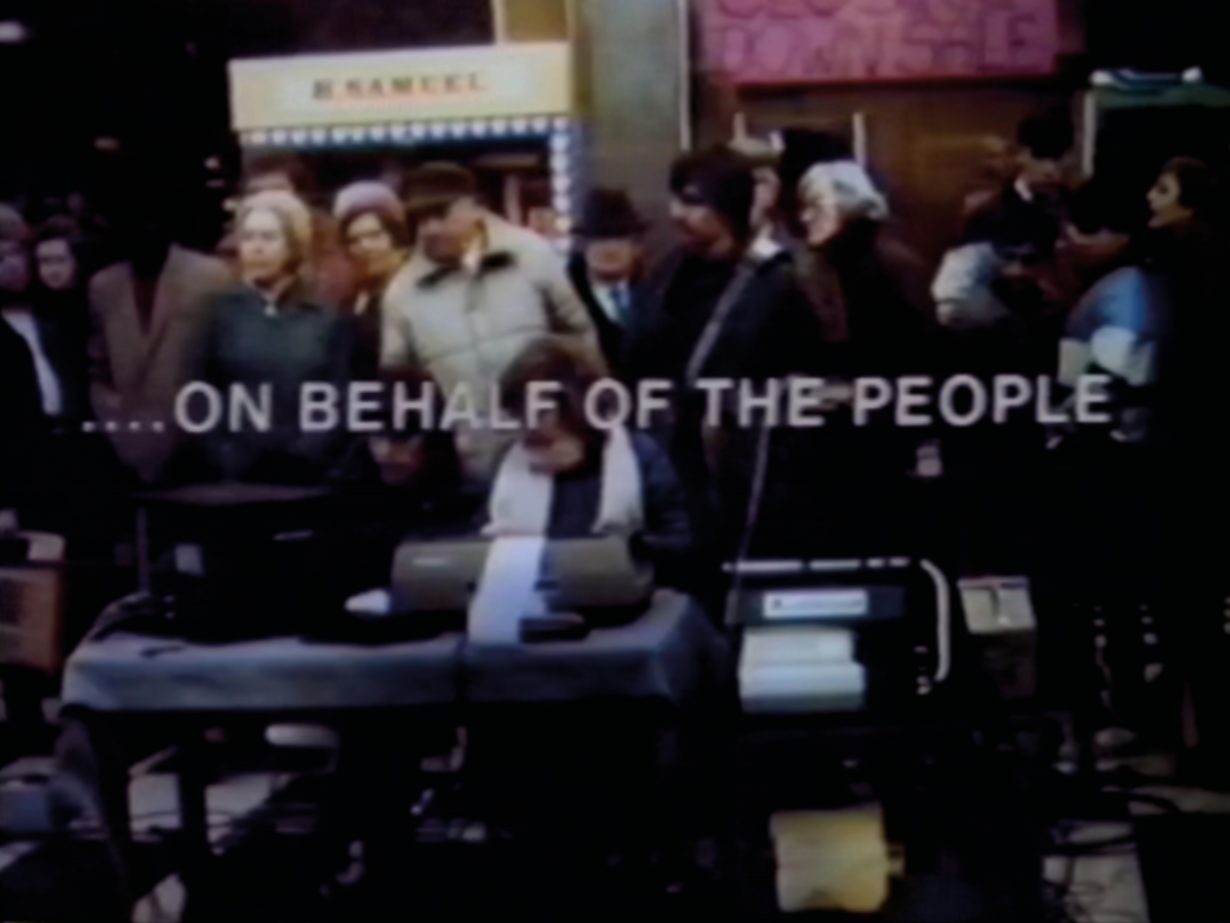

Exhibiting an archive is always a potentially radical act. The past either disappears, or ends up in some unlighted store, waiting for someone to come looking for it, to find its usefulness in the present. Then, it might illuminate how we got here, remind us of past struggles that have faded from memory and urge us to rethink what to do in the present. People Make Television isn’t an art exhibition, it’s an archival display. But it makes the case for how effective the ‘artworld’ can be by creating a space in which archives can be revisited. It’s a singular experience, winding back 50 years to the broadcasts made out of groundbreaking experiments in public and community broadcasting that took shape in Britain during the 1970s. Focused mostly on programmes produced by the BBC’s Community Programming Unit – the series Open Door, which ran from 1973 to 83 – as well as the more fragmentary recordings of a group of mostly shortlived community cable-TV stations (born, ironically, out of the then conservative government’s desire to open up broadcasting to the free market), the exhibition offers an alternative view of Britain during this uncertain, conflicted and often gloomy decade. And those views develop from the wildly divergent viewpoints of various community associations, single-issue campaigners, pressure groups, ex-hippies, anarchists, trade unionists, black rights activists, feminists, racists, punks and a fair number of cranks and weirdos. All of it presented in a galleryful of CRT monitors, in side galleries and in an on-demand viewing space that collectively contain more than 50 hours of programming.

Open Door was the BBC’s response to a growing debate over a more democratic control of broadcast media – inspired by the earlier examples of public broadcasting that had emerged in the US and Canada. It aired a hundred programmes in total, chosen from an open call that attracted hundreds of applications. Though editorial judgement was handed to the groups making the programmes, the BBC’s anxiety about handing over that authority is manifest in the rules it imposed to contain it: that makers should not represent or promote a political party, or pursue an industrial dispute; that they should not incite ‘racialist feeling’ or ‘violent or unlawful action of any kind’.

So, while in People Make Television the archive is presented as a neutral fact, in the background is the constant presence of editorial power, emanating from the monolith that is the state broadcaster. Nevertheless, that filter, despite itself, draws our attention to the emerging character of the new cultural and political forms that, seeded during the 1970s, have come to define and dominate politics and culture now.

Because, if there’s more here than merely a vicariously enjoyed retro vibe in seeing 1970s men’s weird beards and flared jeans and shirt-collars, and 1970s women’s hairstyles and jangling earrings, alongside hessian studio-backdrops, dingy pubs, earnest discussion groups, Aran knitwear, clapped-out Austin Leyland cars, old-school policemen’s uniforms and incessant on-camera smoking, then it lies in the shock of realising how the once-marginal views of the 70s have become the dominant views of the 2020s.

Most remarkable here is the episode made by the Transex Liberation Group (4 June 1973); presented by four trans women, it’s an unprecedented demand for better recognition of transsexuals (the term current at the time), and for a more sympathetic treatment of the problems faced by men and women who understand themselves and want to live as the other sex. Harbinger of pretty much all the points at stake in current gender debates – of the male and female brain, of gender fluidity, of the demand for the state’s formal recognition – it’s also weirdly prophetic of the conflicts now raging: in the closing moments of the studio discussion, one guest, a male clinician, wonders why there are “no women” in the discussion, and recognises that “Women’s Lib will be very angry”.

Elsewhere, there are shows by environmentalist designers complaining about overproduction and overconsumption, warning that we should conserve the resources “we’re currently expending at a rapid rate”; by black teachers castigating the white educational establishment for framing black schoolchildren as “problems”; by Central London neighbourhoods fighting the encroachment of a property developer whose buy-up-and-run-down strategy has destroyed their communities; by the Work and Leisure Society, advocating for the economic good-sense of everyone working only a thousand hours a year; by the anarchist Albion Free State collective, whose groovily spaced voiceover heralds its communitarian utopia of “dancing, and music, and nakedness, and workshops and crafts and food co-ops”

– though with the strangely time-warped coda that we “take back control, from capitalists, corporations and the Eurocrats in Brussels”.

If the progressive ideas seeded in these little groups of the 1970s now shapes the mainstream, what remains unchanged is the political urge to centralise control over the media. Unsurprisingly, the one episode to cause ructions was that of the Campaign Against Racism in the Media, a knife-sharp analysis of the overt and covert racial bias in the BBC’s own output led by a sardonic Stuart Hall in 1979. Similarly, by 1983, the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom was skewering the BBC’s veiled side-taking as Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government took on union strikers. It’s not hard to suspect that such embarrassments to the national broadcaster’s supposed ‘impartiality’ had something to do with Open Door finally shutting, on 30 March 1983, a few months before Thatcher’s landslide reelection.

For all the exhibition’s optimism about the prospect of ‘a participatory and civic television’, it was always the power of the establishment that was at stake. Meanwhile, the identity politics that took root during the 1970s threatened that power perhaps less than the militant working-class politics that met its defeat in the same period. Indeed, so little was the threat, identity politics has in some real sense become the establishment. To this we could add that the ‘participatory and civic television’ that People Make Television suggests never quite happened is in fact here – only it’s on the little screens in our pockets, networking people together, all talking about what they want to talk about. Sure, social media may now be poisoned by capitalism, but it frightens the political establishment to its core. Which is why mainstream politicians of all stripes are desperate to contain, regulate and censor it.